SKIN CANCER

Skin cancer occurs in three forms. Basal cell carcinoma, Squamous cell carcinoma and Melanoma. The malignant significance of each form increases in this order just as the incidence of occurrence decreases. We develop Basal cell cancer four times more frequently than Squamous cell and sixteen times more often than Melanoma. This is most fortunate as untreated Melanoma is one of the most lethal forms of cancer. All skin cancers evolve as mutations of skin cells damaged by solar radiation. Basal cell and Squamous cell cancers occur in previously normal cells of the most sun-exposed parts of the skin. Melanomas arise from the melanin pigmented cells of preexisting birthmarks commonly called 'moles'.

Our individual susceptibility to development of skin cancer varies dependant on one's own skin complexion coupled with one's personal habits of sun exposure. The fairer one's skin the least resistant it is to cancer-producing solar radiation. The greater the history of sun exposure and particularly of sunburns, the higher the occurrence of skin cancer. The observed incidence of skin cancers in Australia is one hundred times greater than in the same racial stock in England-Ireland. The excess of sun exposure is the instrument causing this increase in an otherwise similar skin type baseline.

Basal and squamous cell cancers evolve slowly indicating a twenty to thirty year tail of biological sun abuse as the cellular mutation process evolves into full-blown cancer. The basal cell cancer occurring at fifty has been forming in sun damaged skin from one's twenties. Basal and squamous cell cancer is most often preceded by changes of actinic (sun) damage which appears as dry, flaking patches of pink to red skin of the face, hands or legs. These areas are the precursor of subsequent skin cancer.

ACTINIC KERATOSIS

If actinic keratoses can be recognized while still in the precancer stage they may be treated with various forms of sclerosis such as liquid nitrogen or cautery desiccation. Many patients with severe solar skin damage will benefit from a topical course of Efudex (5 Fluoro-Uracil) in an attempt to burn away the more rapidly dividing precancerous cells before they fully mature into invasive cancers. This is a diagnostic decision to be made under direct supervision by a dermatologist or surgeon. Recognition of the physical differences between severe solar keratoses and evolved skin cancer is difficult and it may be safer to remove an advanced actinic keratosis rather than allow it to progress. It is believed that the evolution of actinic keratoses is to squamous cell cancer rather than basal cell, but I have observed it to produce either type.

Melanoma may evolve gradually, signaling its early evolution as a darkening of color or irregularity of shape of a previously bland-looking birthmark. Rarely, melanoma can flare up almost overnight as a result of an acute sunburn. Melanoma may also occur in moles that are hidden in places of our bodies that never see the light of day, and we don't know why. Melanoma appears in younger decades of life as a more virulent form as well as the slower maturing type seen in older skin. These observations indicate additional biological triggers as well as genetic factors for the causation of melanoma.

Treatment of skin cancer is the most frequent surgery performed in my plastic surgical practice. Annually over six hundred patients are treated by primary surgical excision. Although skin cancer may be treated by radiation or dermatological curettage, its common occurrence on the face or on other visible parts of the body calls for both skilled and assured removal, combined with a cosmetic closure or reconstruction of the involved facial or body part. This is the essence of plastic surgery which we have been trained to perform. Most often this involves a carefully designed and adequate elliptical excision, which must include a border of uninvolved tissue. This is planned to align with the lines of facial animation. Larger cancers in critical anatomic areas may require tissue coverage by skin flap or skin graft replacement. Each of the three types of skin cancer demand increasingly wider borders of removal to assure adequacy of cure. Radiation is ineffective for melanoma.

BASAL CELL CARCINOMA

The most common and least dangerous form of skin cancer arises in the deeper or "basement-basal"; level of the skin. It erodes locally in the area of origin and may ulcerate and destroy adjacent tissue, but it does not spread or ‘metastasize' to distant parts or organs of our body. Untreated basal cell cancer can be most destructive to local structures but will not cause death.

Basal cell cancer occurs in five physical forms of which the first three are the most commonly seen cancers in America: 1) Superficial spreading type characterized by a persistent red-pink spot which gradually enlarges; 2) Nodular type which appears as a new pearl-like bump anywhere on the face or trunk; 3) Ulcerative type that seems to evolve from a proceeding raised pink mass, which now forms a crater-like central ulcer. The crater edges or borders are pink and pearly. This is also called a "Rodent Ulcer";. The last two forms, rare and subtle to diagnose are: 4) Morphea or scar-like basal carcinoma and 5) the confusing pigmented type which may resemble a melanoma. Patients who have experienced any of the first three forms will be quick to recognize a new lesion. This is particularly important as basal cell cancer having once occurred in a patient will tend to occur again in a new spot as we further age. Our skin continues to harvest the seeds of sun damage sown in the past years of our youth.

TREATMENT OF BASAL CELL CANCER

In my opinion direct surgical excision is the best treatment for basal cell carcinoma. It is the simplest in time, cost and effectiveness when performed by an experienced plastic surgeon. It allows for planned closure of the wound in the most cosmetically effective manner during the same procedure as the definitive excision. Adequate primary excision of evident basal cell cancers of types 1 thru 3 and 5 (see above) require a clear surgical margin of 2-3 millimeters of uninvolved tissue and will cure 98% of these cancers.

Morphea (type 4) is a microscopically infiltrating cancer, which burrows beneath the skin beyond the visual borders, which can be seen at surgery. Such morphea forms, and other occasional types of basal cell which involve a vital structure or have recurred, will be better treated with accompanying microscopic analysis of the cut edges of tumor at the time of surgery in order to assure complete excision. This can be done in a hospital operating room with a pathologist in attendance for frozen section analysis of margins.

MOH'S TECHNIQUE

The combined use of microscopic analysis at the time of tumor removal by dermatological curetting is "Moh's Surgery"; or "Moh's Technique";. This is performed by specially trained dermatologists who read the tissue margins at the time of scraping or curetting the cancer out. They will not stop until every cancer cell is clear. When indicated in very difficult or infiltrating types of cancer, this is the most assured method of removal. It is not "surgery"; and it does not include the wound closure or repair. Closure must still be done after removal is completed. Wounds produced by "Moh's curetting"; are larger and often round in shape. "Moh's"; is a time-consuming and expensive procedure, excellent when appropriately applied to a difficult cancer but not to be overused in straightforward cases of basal cell cancer. Patients are well advised to beware of "Moh's technique"; when offered for treatment of the simplest of skin cancers. In unskilled hands "the whole world looks like a nail if the only tool available is a hammer."

SQUAMOUS CELL CANCER

This second form of skin cancer arises in the surface cells, the squamous epithelium which is the outer or finished layer of our skin. The cause of squamous cell cancer is the same as basal cell: solar and environmental radiation. Additionally, squamous cell cancer may arise in a chronic burn or wound scar and is then called Marjolin's Ulcer. Solar or X-radiation causes gradual mutation of dividing cells which first deviate from normal but then evolve completely into cancer. The effect and appearance of squamous cell cancer is far more malevolent. Once developed to sufficient size this cancer may spread to other parts of our bodies by lymphatic and blood vessel dissemination. This process of metastasis further complicates the otherwise similar action of local tissue destruction as occurs with basal cells. A distant metastasis will grow invasively and destroy the organ to which it has spread. Squamous cell cancers grow more rapidly, are uglier and larger than their counterpart basal cell tumors and require a more extensive margin of removal.

Earliest squamous cancer appears as a non-invasive (non-metastasizing) superficial form, which arises within preceding actinic keratosis. This form is called "Bowen's Disease"; for the pathologist who recognized it. It may be treated more conservatively with a narrower margin of excision or even with Efudex as used for actinic keratoses. The problem again is recognition. The greatest number of these is surgically excised with good outcomes as our treatment course is based on worse case expectation.

Larger squamous cell cancers take much the same physical forms as basal cell, only in each case more pronounced. They may form as tumorous masses or thick crusty growths but in both forms seem to outgrow their blood supply, rapidly progressing to unsightly ulceration. Early squamous cell cancer may mimic the nodular-ulcerative form of basal cell cancer. The distinction in diagnosis is important, as surgical excision of squamous cell cancer requires a wider margin of clear tissue removal. Patients with large advanced squamous cell cancer must be surveyed for distant spread of their disease. If found, such metastases require treatment as well. The necessity for wider margins of excision in squamous cancer often leads to the need for skin grafts or local tissue flap transfers to close larger wound defects. Such procedures test the plastic surgeon's skill to its highest degree.

Clinical Examples of Grafts/Flaps/Adjacent Tissue Transfers

MELANOMA

The majority of melanomas arise from preexisting birthmarks, which undergo malignant transformation. Patients are struck with disbelief that a small brown mark they have seen and known all their life can suddenly be threatening them vitally. This complicates the necessity for early detection and causes untoward disbelief in patients coming for treatment. Understandably they hesitate to accept wide surgical excision as treatment for such a seemingly innocuous spot. Yet of the three skin cancer types, untreated melanoma is the most deadly. Advanced melanoma is responsible for 75% of the deaths from skin cancer. This has led surgeons to adopt an early aggressive surgical approach to any changing birthmark in an attempt to beat cancerous transformation to the punch.

DYSPLASTIC NEVUS

Any birthmark showing a change in shape, size, color or irregularity of border should be examined by your doctor and removed for biopsy. As a treating surgeon, I have come to believe we should be excising 1000 pre-cancerous nevi (birthmarks) to preempt one overlooked melanoma. Most often we find early changes differing from the appearance of normal pigment cells. The pathologist describes these as dysplasia or atypia. Such cell changes are the first indication of mutation in the direction of melanoma. They are not yet cancerous but are a stage in the evolution to cancer. Atypical melanin cells often surround established melanomas which arise in their midst, demonstrating the biological progression from this precursor change. No one knows the biologic time span to complete transformation but we'd rather not wait to allow its occurrence. A patient who has been found to have a dysplastic nevus should be seen by a dermatologist at least once a year for periodic body checks as well as being self-conscious of any additional new changes in other existing birthmarks.

There is a rare genetic condition, Dysplastic Nevus Syndrome, in which members of a family develop multiple changing nevi that lead to melanoma at an increased rate of occurrence. When possible such patients are identified as early as adolescence. They have a family history of melanoma in a parent and show clusters of small flat-pigmented spots (junctional nevi) over diffuse areas of the trunk or limbs. Each newly darkening pigment spot should be excised and biopsied when first recognized.

MELANOMA STAGES

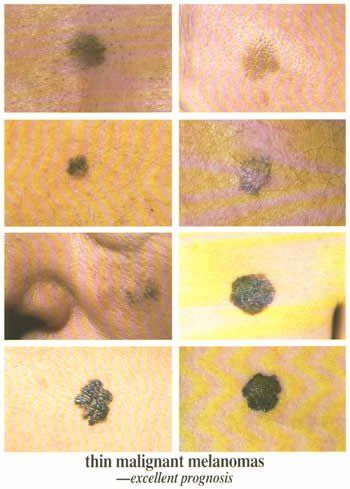

STAGE I | Early melanomas spread outward on the skin surface before they begin to invade the deeper levels of the dermis. At this stage they are completely curable by wide surgical excision, as they have not yet penetrated to a depth which produces spread to regional lymph nodes. Microscopic measurement of the thickness or depth of such melanomas is less than 1.0 millimeters (1/16th inch). These are Stage I melanomas. We would wish to find and excise every developing melanoma at or before this stage as there would be no deaths from such early treated melanoma.

A lesser form occurs in older patients known as Melanoma In-situ. Here the earliest melanoma cells just begin to spread along the surface of the epidermis but do not yet invade at all. Such melanomas could be considered Stage 0.5 as they are the very first cancerous change seen in melanoma. They are cured by excision as well. The goal of early detection and complete excision is to find and treat every possible melanoma at or before Stage I.

STAGE II | Melanoma penetrates 1.0 to 4 millimeters into the deeper layer of the skin dermis. It does not yet show clinical spread to regional lymph nodes, but tumors of this depth are now tested by radioactive dye injection tracing their drainage pathway to the nearest anatomic lymph node. This "sentinel node"; may be biopsied to determine whether it shows microscopic involvement, which would then upgrade the staging to the next level. If negative, Stage II melanomas treated by wide surgical excisions have a 90% ten-year survival rate.

STAGE III | Melanoma is deeper than 4 millimeters and has penetrated into tissue below the deepest level of the skin. Melanoma cells have spread to the adjacent lymph nodes. There may be additional "satellite"; pigmented tumors on the skin around the original growth. At this stage melanoma has already escaped from its site of skin origin. Treatment is by wide surgical excision and may be combined with removal of the adjacent involved lymph nodes. The statistical chance for cure falls to significantly less than a 70% ten-year survival.

STAGE IV

| Melanoma has all the above and has spread to distant sites or organs far from the place of origin. The prognosis for cure is dire.

Beyond surgical removal there is neither current chemotherapy nor radiation therapy which assures successful cure. There are many experimental approaches using immune enhancement agents, which may slow or change the course of Stage III and IV melanoma but not cure its ultimate outcome.